“The Disuted Territory” Shown in green is Kashmiri region under Pakistani control. The dark-brown region represents Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir while the Aksai Chin is under Chinese occupation. Source: Wikipedia citation of the CIA World Factbook

“The Disuted Territory” Shown in green is Kashmiri region under Pakistani control. The dark-brown region represents Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir while the Aksai Chin is under Chinese occupation. Source: Wikipedia citation of the CIA World FactbookBennett Ramberg, in an opinion piece for the Christian Science Monitor, suggests for India to let Kashmir go: “options include independence, division along communal lines, comanagement by both India and Pakistan, [or] a UN trusteeship.”

It is generally easy for an outside observer to discuss giving away someone else’s percieved property, rights and claims. How easy it can be for us to tell someone else, “All you need to do is give up what you’ve been struggling over for generations.” The more difficult thing to do is for each party to consider what is best for the other parties involved, as well as consider their own interests. New equilibrium outcomes can only be likely when opinions are open to new considerations. Otherwise, mentalities and opinions will likely go back to pre-existing expectations and de facto schemas.

Kashmir: A Reverse Land for Peace Deal?

“Let it go.” This simple-sounding axiom, couched by the citation by Ramberg of the amicable division of Czechoslovakia, and the mostly peaceful dissolution of the Soviet Union, is not so easily cut-and-dried. The Czech Republic and Slovakia were both swept into a ready-and-waiting strong neighborly brotherhood of the EU and NATO. There were extremely wealthy vested interests in seeing this be a friendly, happy, and amicable divorce. The same was certainly not true for nearby Yugoslavia, which, once the pins were pulled out of its national structures, turned into a decade-long tragedy.

Having India let Jammu and Kashmir go would be far more akin to the Arab-Israeli “Land for Peace” consideration. Which, like the Kashmir question, has historical roots in conflicts that broke out in the post-World War II division of lands between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Yet as Ramberg himself points out, Indian wargaming strategies show a reverse “land for peace” deal is more likely. Under the Indian “Cold Start” strategy, India would seize Pakistani border territory in a rapid strike. Then, it would put pressure on Pakistan to meet its demands for the withdrawal from Pakistani territories.

In other words, the same sorts of territorial disputes that followed the Arab-Israeli 1967 war might await the region in a future Indian-Pakistani conflict. It would be an inverse of the 1999 Kargil War, where Pakistani units infiltrated and held onto territory in Indian-controlled Kashmir. Yet that conflict pushed the prospects of nuclear war to the brink. Pakistan’s government is still extremely unstable. Such conventional warfare might result in utterly horrific casualties if violence spiralled out of proportion.

Does It Matter Who Runs Kashmir?

Yes. Apparently.

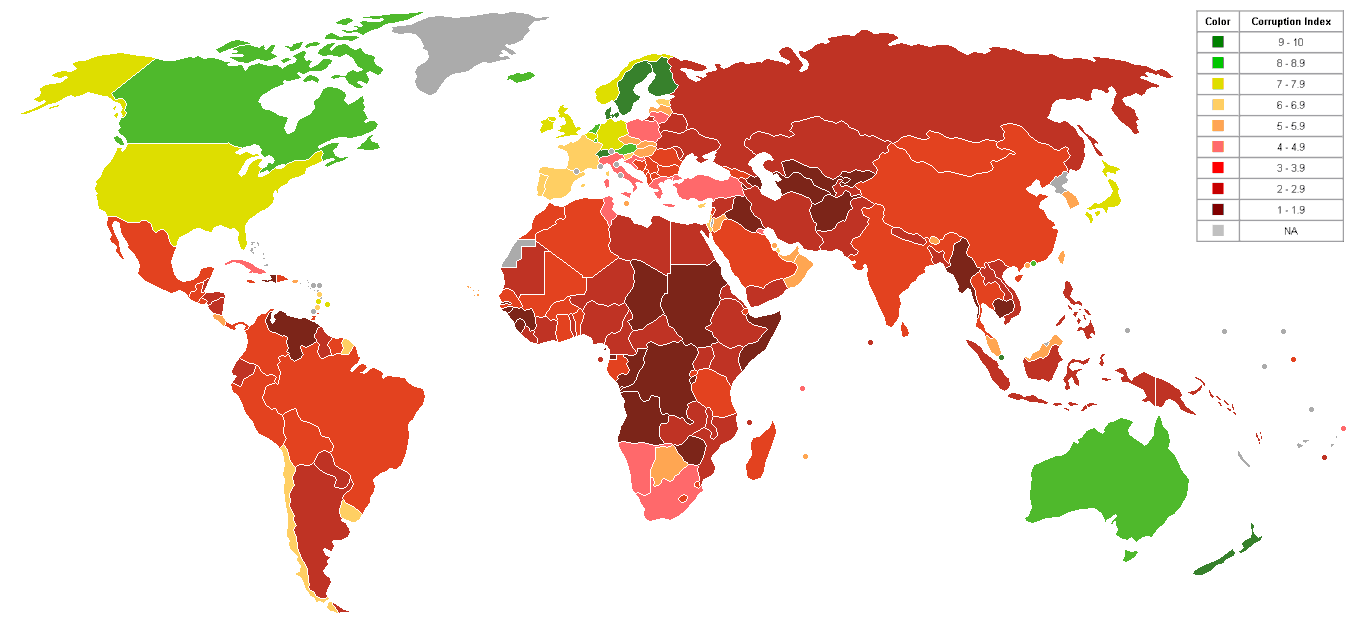

Both the Indian government and Pakistani government are infamous for corruption, negligence, self-serving deals, fratricidal political infighting, veiled (and not-so-veiled) use of violence, and, of course, crass nepotism. Pakistan is ranked as low as #134 out of 180 nations in the world in terms of corruption; India at #85, though mis-management in Jammu and Kashmir is specifically noted as extreme. It is the most-corruptly administered area of the Indian nation.

Mind you that the governments of India and Pakistan are seen, regionally, to be some of the less-corrupt governments in south Asia. Add to that the numerous wars fought between the two nations since 1947, and you can see the reasons for distrust.

Thus, to a great degree, much of the lack of trust boils over into not wanting the other side’s corrupt politicians getting their greedy hands on the territory. Instead, both nations feel comfortable that their own corrupt political machines can rule over Jammu and Kashmir, while the other nation’s bureaucracy is exoriated and derided.

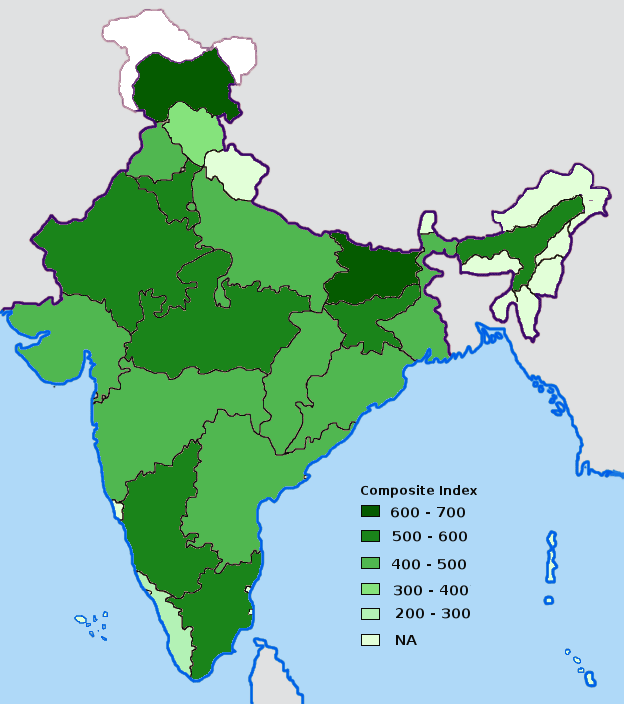

Index of Corruption in Indian states in 2005;

Index of Corruption in Indian states in 2005;Note Jammu & Kashmir in the north is the most corrupt.

Source: Wikipedia

Pluralism: It Begs the Question

At its heart, there lurks the fundamental issue of pluralism: whether there can be peaceful co-existance of different religions and ethnicities in these territories. It would matter less which nation administered these territories if the rights of various populations were respected, and services guaranteed on a basis of civil equality.

So long as there is distrust, and indeed, a fair basis for the common people of the region to believe there is good reason to not trust politicians of either government, there will be the resultant undermining from below, oppression from above, forces exploding out from the middle, or a society collapsing in upon itself. There can be no stability regardless of which national government seeks to establish suzerainty over the territory. Furthermore, a region left in “free fall” will find neighbors pumping in money, leadership, and elements of control to seize power.

It should be noted that a strong external government cannot necessarily enforce a strong local result. For instance, since the United States intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq, their national institutions have floundered horrifically. Afghanistan ranks #176, and Iraq at #178 on the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index for 2008, out of 180 nations ranked. They are in the company of such basketcase nationstates as Somalia, Haiti and Sudan.

Pulling out a strong national government does not necessarily equate to peace and stability in terms of residual institutions. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a few former republics have fared well, yet Tajikistan (tied for #151 place), Azerbaijan (#158), Kyrgyzstan (#166), Turkmenistan (#167), and Uzbekistan (#168) have fallen precipitously and become very corrupt states.

It is no guarantee a simple pullback of India from the area would guarantee peace and stability. Much the same way that a pullout of Lebanon by Syria and Israel did not guarantee, immediately, a functional state. While Lebanon is waveringly rising from the impoverished state it was reduced to by decades of civil war, much violence and tension remains. Further, there was never a consideration of Lebanon being a province of Syria or Israel.

Instead, Kashmir might be more likened to the Palestinian territories, which were once claimed by Israel. Yet this is not precisely a model of a stable, friendly independent state along the withdrawing power’s borders. Such models bode poorly for India’s northern border were Kashmir made independent.

What Do Indians Want?

According to a Times of India article, dated 23 August 2008, 59% of Indians believe “India should hold on to Kashmir despite the economic cost of doing so.” 11% were undecided. 30% said the cost of doing so was already too high.

The most telling statistic was that 68% of Indians believed Kashmir should not be allowed to secede from India even if it wanted to. To them, alienating Jammu and Kashmir would be akin to the United States allowing one of our own fifty states to withdraw from the nation.

This survey showed that about 30% believe the cost of holding on to Kashmir is already too high. A minority opinion of about that proportion might theoretically support Kashmir’s independence from India. According to the Times of India: “At one level, it indicates that what was simply not thinkable until now - whether Kashmir could secede from the Indian Union or not - has possibly become a matter of debate, even if it is within a small section of our urban society.”

However, the same study also showed that only 19% felt such a move would make the country more secure. 31% felt it would make no difference to Indian security—threats, such as terrorism, would remain regardless of whether Kashmir went its own way or not. “As for fear, a clear half said India would become a less safe place if Kashmir were allowed to secede. In other words, the terror threat to the country would only increase if the northern border were to come closer to the country's heartland.”

Instead, the predominant opinion, held by more than 75% of those surveyed, felt Kashmir could still be integrated into the mainstream of Indian governmental organization and social structure.

Amongst these surveyed Indians, 41% felt that Kashmir had been neglected by government. 30% felt Kashmir had been treated fairly, and an almost equal number, 29%, felt it had been pampered.

Pakistani Concerns

Pakistani opinions are very fractious now, far more than India. The nation is facing a low-grade internal civil war, or at least, autonomous state withdrawal from central administration. It is possible India might need to intercede along the Pakistani border for better security if military or paramilitary organizations went rogue and decided to spill violence over the border into India.

Pakistani military involvement, though denied, has been detected in schemes using now out-of-control paramilitaries from the Kargil War to the recent Mumbai bombings. It calls into question how much respect there is for civil government, versus the state of “vae victus” — Might Makes Right.

India’s internal impetus to public opinion is increasingly calling to cross the Pakistani border to seek vengeance for what happened in Mumbai in November, and in other attacks over recent years. So far, India has shown some restraint in light of repeated attempts of provocation by Pakistan going back to the strategically-planned Kargil War of 1999. Though the Kargil War was a devastating set-back for Pakistan, the persistance of provocation is not lost on India.

Cloudy with a Chance of Peace

Both Indian and Pakistani zealots are pushing for war with each other. Both Indian and Pakistani moderates and doves are attempting to broker peace. Right now, much hangs in the balance. The militants on both sides know this, and they are, in a way, allies in encouraging violence. India continues to back independence-minded rebels in Baluchistan, while Pakistan continues to sow seeds of dissent over Kashmir. How far might both sides push each other?

A Reuters article today outlines some of the possible effects such a conflict might cause. Pakistan has been considering counters to the Cold Start scenario for years. The recent movement of tens of thousands of troops to the Indian border is likely a preventative measure to ensure territorial sovereignty in light of such a policy.

Yet all these actions and responses seem practically polite compared to the nuclear exchange scenario written about by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), which authored a study in 2002 about The Consequences of Nuclear Conflict between India and Pakistan. Numbers killed by nuclear exchange ranged between 3 million (using Hiroshima-sized bombs) to 30 million.

Such conflict would not likely be limited to nuclear exchange. Such a catastrophe might lead to full-scale conventional war as well. It could also lead to internal civil war or insurrection inside both Pakistan and India. Hence why both nations are hesitant, even as radical elements of both nations call for responses. Both nations are already facing increasing internal chaos, such as that which Pakistan faced during the aftermath of the assassination of Benazir Bhutto.

The burden of solutions now rests squarely in the shoulders of moderates in both nations. If they are able to navigate a path to peace, between Pakistan and India on a broader scale, only then can the Kashmir question be raised for conclusive resolution. Otherwise, it will remain a pawn on the board of geopolitics, never truly free because the two states that determine its fate will claim it, or portions or whole swaths of it, when their sovereignty or security are threatened.

No comments:

Post a Comment